Samarkand had lived in our imagination long before we ever stood inside it. The name itself carries a quiet weight — one that appears repeatedly in books, maps, and stories of empires, trade routes, and scholarship. Yet, as with many places shaped by centuries of history, Samarkand reveals itself less through grand introductions and more through layers that slowly unfold over the course of a day.

Our first morning began with one of those places where history feels both monumental and unexpectedly intimate — the Gur-e-Amir, the mausoleum of Amir Timur.

The structure rises with a composure that feels deliberate rather than imposing. Its deep azure dome, decorated with intricate mosaic work, seems almost weightless against the sky. Inside, the atmosphere shifts immediately. The interiors glow with turquoise, gold, and calligraphic details that draw the eye upward rather than inward. The patterns are elaborate, yet there is restraint in their repetition, a rhythm that feels almost meditative.

At the centre lies the dark jade tombstone marking Timur’s resting place — austere, almost understated when set against the richness surrounding it. It is a reminder that empires often leave behind both spectacle and silence in equal measure.

From there, Samarkand opens outward into one of the most recognisable spaces in Central Asia — Registan Square.

Standing within Registan is less about observing architecture and more about being surrounded by it. The three madrasas — Ulugh Beg, Sher-Dor, and Tilya-Kori — do not compete with each other; instead, they create a dialogue across centuries. What was once a marketplace and centre of public life now feels like a preserved memory of intellectual ambition.

The Ulugh Beg Madrasa, built in the early fifteenth century, carries the legacy of a ruler who was as much an astronomer as he was a sovereign. The later Sher-Dor Madrasa introduces a rare departure from traditional Islamic ornamentation — mosaics depicting tiger-like creatures bearing sun motifs across their backs. The imagery feels bold, almost playful, and speaks of artistic confidence rather than strict adherence to convention.

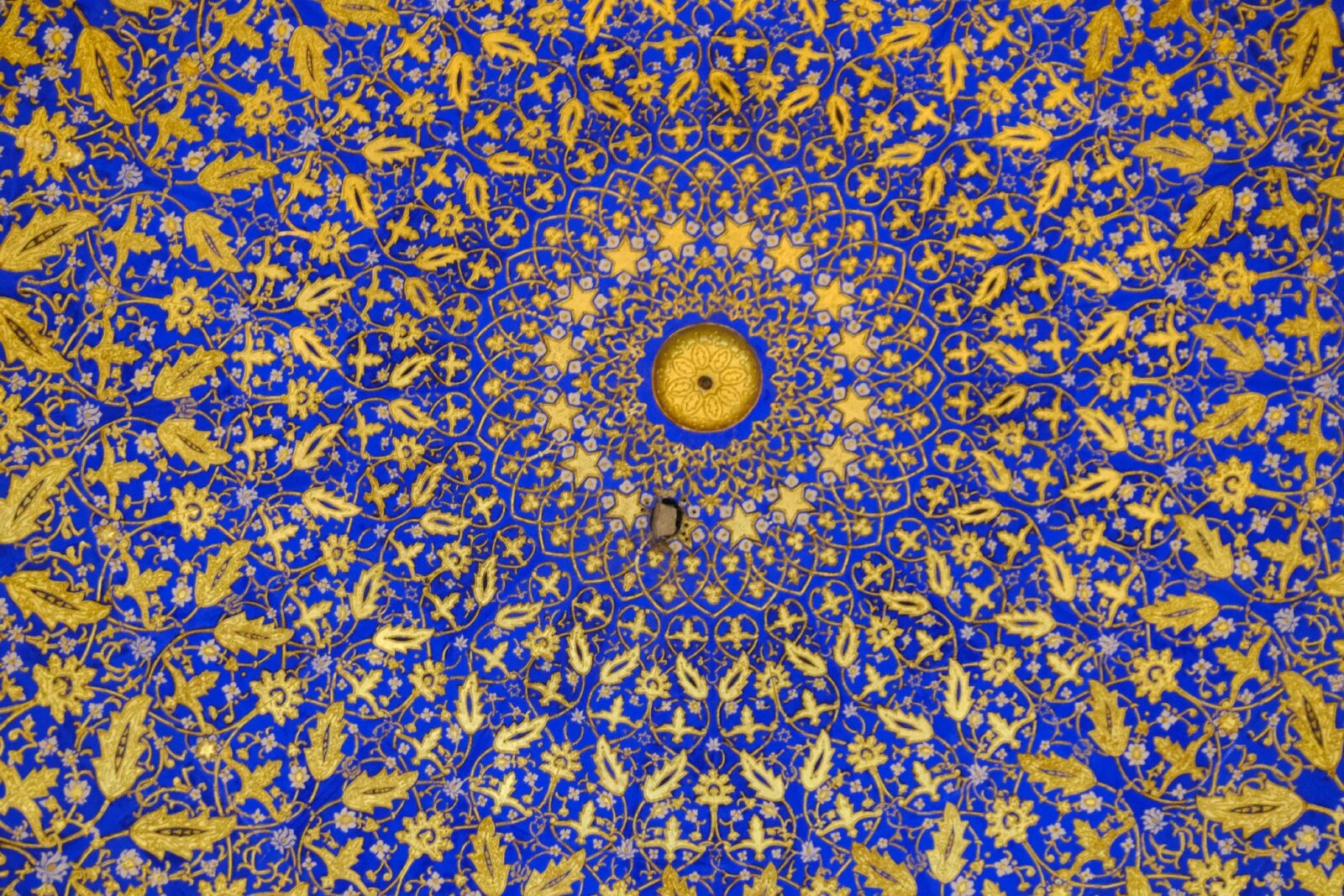

Inside Tilya-Kori Madrasa, the gilded dome of its mosque transforms the interior into something almost celestial. Gold leaf patterns radiate outward in a way that creates an illusion of endless symmetry. The light shifts constantly, altering the atmosphere within the chamber with each passing moment.

Later in the day, the scale of monuments gives way to the rhythm of everyday life as we move towards Siyob Bazaar.

Markets often reveal more about a place than its monuments, and Siyob is no exception. The air carries the fragrance of spices, dried fruits, and freshly baked bread. Conversations flow easily between vendors and visitors, often accompanied by curiosity that is both direct and unfiltered.

It was here that we encountered a group of schoolchildren who approached us with a mixture of enthusiasm and earnestness. Their first questions were predictable — where we came from, how long we were visiting. But the conversation quickly shifted in an unexpected direction when one of the boys, with the sincerity only children possess, declared that Islam was the best religion and suggested that we should convert.

The moment felt awkward rather than confrontational, surprising mainly because it came from someone so young. Thankfully, the tone softened almost immediately as other children joined in, speaking about the subjects they studied and mentioning that India was part of their curriculum. The conversation moved naturally towards laughter, photographs, and good wishes before we parted ways.

It was one of those encounters that lingered — not as judgement, but as a reminder of how identity, education, and curiosity intersect in ways that are often more complex than they first appear.

Not far from the city lies the village of Konigil, where another dimension of Samarkand’s legacy continues quietly — the craft of traditional paper making.

Mulberry bark is stripped, soaked, and beaten into pulp before being spread into delicate sheets and dried under the sun. Once dry, the sheets are polished with smooth stones to create a texture that feels both durable and refined. Watching the process unfold slowly reveals how knowledge once travelled not only through scholars and caravans, but through materials shaped by patient hands.

Konigil today functions as a cultural heritage space, preserving crafts that once supported Samarkand’s reputation as a centre of learning and trade along the Silk Road.

Konigil also reminded us that Samarkand’s legacy was never built only by rulers or scholars. It was sustained by artisans whose work travelled silently across continents. Watching sheets of mulberry paper dry under the winter sun felt like witnessing knowledge in its most tangible form — fragile, patient, and enduring.

By the time we returned to the city, evening had begun to settle in. As the temperature dropped, we found ourselves drawn back to Registan, this time to watch the monuments under artificial light. The transformation was subtle but powerful. The same structures that had dazzled in daylight now appeared calmer, almost introspective, as warm lighting traced their arches and mosaics.

Later that evening, as the winter chill deepened, we lingered in the square longer than we had planned. It was there that we met another Indian couple, originally from Kerala but now settled in Delhi. The familiarity of shared cultural references made the conversation effortless despite the cold. She was a schoolteacher, he worked as a consultant, and like us, they travelled within the small windows that work and routine allowed.

What began as casual introductions soon turned into an extended conversation about travel choices, history, and the quiet motivations that draw people repeatedly towards places like Samarkand. The cold eventually forced all of us to part ways, but encounters like these have a way of attaching themselves to memories of a place as strongly as its monuments.

As we left Registan that night, it felt less like we were leaving a historic square and more like we were stepping away from a living archive — one shaped equally by empire, scholarship, craftsmanship, and the countless travellers who continue to pass through it.

Leave a Reply