If our first day in Samarkand unfolded through imperial grandeur and public spaces, the second morning felt quieter, almost introspective. The monuments we visited now spoke less of power and more of knowledge, memory, and devotion — the less visible foundations of the civilisation that once flourished here.

Our day began at the Ulugh Beg Observatory, a reminder that Samarkand was not only a political centre but also one of the intellectual capitals of the fifteenth century.

Ulugh Beg, grandson of Timur, was unusual among rulers of his time. His legacy rests not on conquest, but on scholarship. The observatory he built was among the most advanced astronomical centres of its era. Today, little remains above ground. The surviving portion of the massive sextant lies partially buried, revealing only a fragment of what was once an extraordinary scientific instrument.

Standing beside those remnants, it becomes difficult not to reflect on the ambition required to measure the heavens with such precision centuries before modern technology. The site does not overwhelm visually; instead, it invites contemplation. It quietly tells the story of a civilisation that invested deeply in understanding the universe as much as ruling territories.

From the observatory, we moved towards the mausoleum of Saint Daniel — known locally as Hazrat Daniyar — a site regarded across multiple faith traditions. The narratives surrounding Daniel differ depending on cultural and religious interpretation, but perhaps that ambiguity is what gives the place its quiet universality. Here, he is remembered as a figure connected to three religions, and the mausoleum reflects that layered reverence without needing to explain it.

The setting itself is strikingly scenic, with the structure stretching gracefully along the riverbank. The landscape softens the presence of the shrine, making it feel less monumental and more contemplative. Visitors arrived steadily — families, pilgrims, travellers — each interacting with the space in their own unspoken way.

While we were there, a local family approached us, smiling and asking if they could take a photograph with us. It was one of those gentle, spontaneous interactions that seem to happen frequently during travel, where curiosity is expressed with warmth rather than hesitation.

Not long after, the call to prayer echoed across the surroundings. The atmosphere shifted almost instantly. Conversations faded, movement slowed, and we found ourselves sitting quietly, instinctively respecting the moment and the rhythm it brought with it. It was not our ritual, but it was easy to understand the stillness it created.

Standing there, it became clear that Samarkand’s history is not defined solely by rulers or scholarship. It is also shaped by belief systems that travelled, intersected, and settled here over centuries, often existing alongside each other with a surprising sense of continuity.

We made a brief stop at the Afrosiyob Museum, a place that quietly shifts the timeline of the city far beyond its Timurid splendour. The museum sits near the archaeological remains of ancient Afrasiyab — the original settlement that existed centuries before Samarkand rose to prominence.

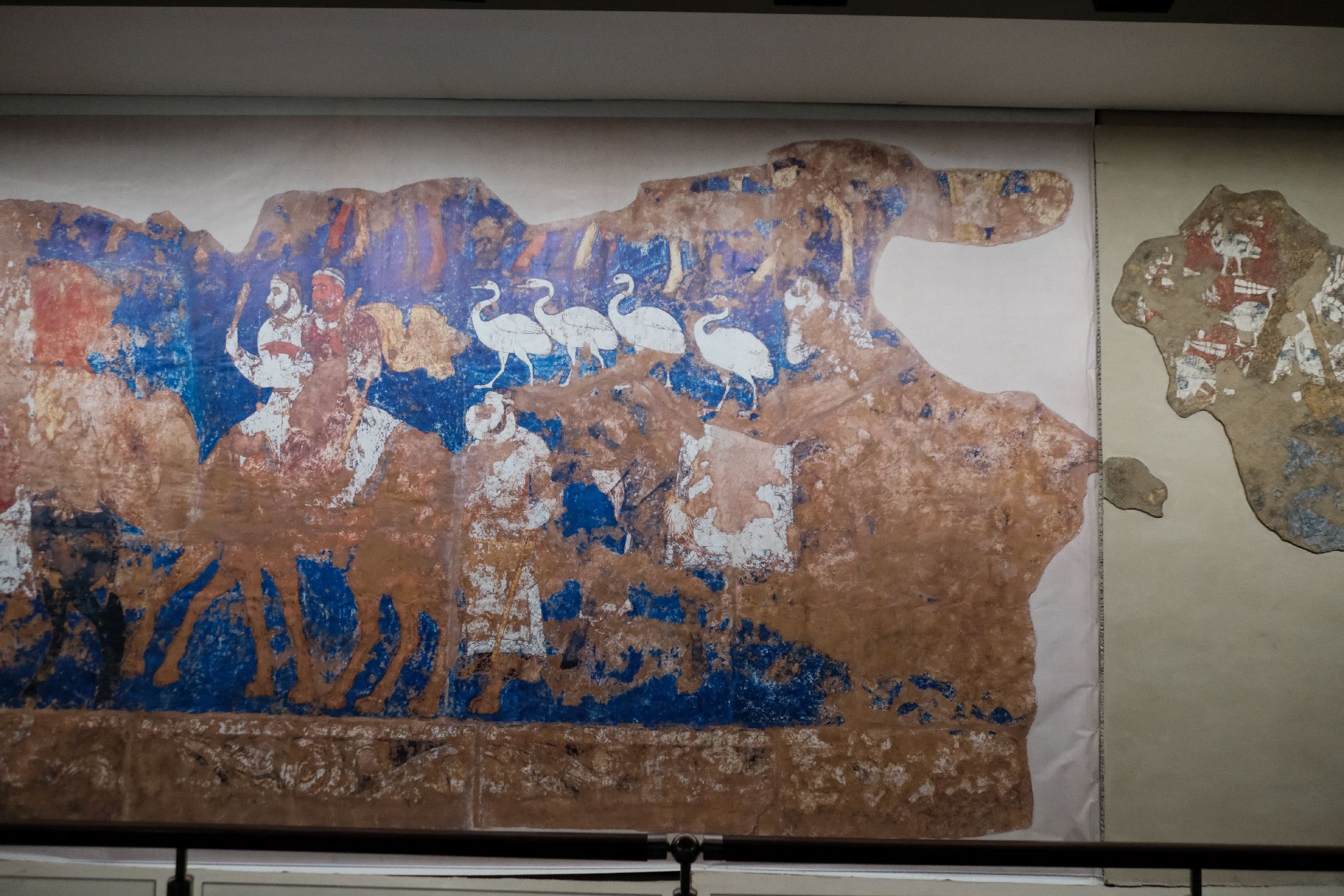

The highlight of the museum is a remarkable wall mural dating back to the 7th century. The faded yet detailed painting depicts diplomatic processions, royal gatherings, and scenes of daily life that hint at Samarkand’s role as a crossroads of cultures long before it became synonymous with Silk Road trade and Timurid architecture.

Standing before the mural, its worn pigments and fragmented outlines seem to carry a fragile continuity of memory. Unlike the restored monuments of later periods, the mural feels raw and unfiltered, revealing history in its incomplete yet deeply evocative form.

The museum visit subtly reframes Samarkand. It reminds us that the city’s identity was never built in a single era. Instead, it evolved through successive civilisations, each leaving traces that survive in fragments, stories, and preserved artefacts.

From there, we travelled to Shah-i-Zinda, a place that shifts the experience of Samarkand from intellectual legacy to spiritual continuity.

The complex unfolds as a narrow avenue lined with mausoleums, each structure carrying variations of tile work in deep blues, turquoise, and white. The craftsmanship is intricate without feeling repetitive. Light plays constantly across the glazed surfaces, altering their tone with every movement of the sun.

Shah-i-Zinda is believed to house the tomb of Qusam ibn Abbas, a cousin of Prophet Muhammad, which makes it one of the most revered pilgrimage sites in Uzbekistan. But beyond its religious importance, the site feels deeply personal. Each mausoleum appears to tell a story not just of individuals buried there, but of the artistic traditions that evolved across generations.

Walking through Shah-i-Zinda feels less like visiting a monument and more like passing through an architectural narrative — one that blends grief, devotion, beauty, and craftsmanship into a single uninterrupted corridor of memory.

Shah-i-Zinda carries an atmosphere that encourages quiet movement, yet it is far from silent. Families arrive together, pilgrims move with deliberate attention, and visitors pause frequently to absorb the intricate artistry around them. While we were walking through the complex, a large local family approached us, smiling and asking if they could take a photograph with us — particularly with P. One by one, from grandmothers to young daughters, they took turns standing beside her, laughing and adjusting scarves and shawls between photographs. The moment felt unexpectedly affectionate and gently amusing for us. Encounters like these seem to emerge naturally during travel here, where curiosity often expresses itself with warmth rather than distance. It was a small, fleeting interaction, but it stayed with us as much as the luminous blue tiles that surrounded us.

Not far from where we stood, another couple was taking photographs along the tiled passageway. They appeared to be an Indian Muslim couple, and the photographs seemed to carry a quiet celebratory intent — the woman was visibly pregnant, and the careful poses and gentle encouragement from her husband suggested it was a personal milestone they wanted to record in a place that clearly held spiritual meaning for them. The scene felt intimate and respectful, blending naturally into the rhythm of families, pilgrims, and visitors who moved through the complex. It was a reminder that sites like Shah-i-Zinda continue to remain part of lived traditions, not only historical memory.

By late afternoon, our time in Samarkand had begun to draw to a close. The city had introduced itself through empire, scholarship, markets, craft traditions, and sacred spaces — each layer revealing a different aspect of its identity.

Our departure from Samarkand came with an experience that felt symbolic of Uzbekistan itself — the Afrosiyob high-speed train connecting Samarkand to Tashkent.

Intercity travel in unfamiliar countries often carries an element of uncertainty, but the Afrosiyob service felt remarkably seamless. Introduced in 2011, these modern trains link Uzbekistan’s historic Silk Road cities — Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara — with efficiency and comfort. Manufactured by the Spanish company Talgo, the train derives its name from Afrasiyab, the ancient settlement that existed in this region long before Samarkand rose to prominence.

The train glides through the landscape at speeds approaching 250 kilometres per hour. Despite its advanced engineering, the experience does not feel rushed. Large windows allow the winter landscape to drift past in long uninterrupted stretches, occasionally revealing small settlements, open fields, and distant silhouettes of mountains.

At times, subtle vibrations appear as the train moves across older sections of track, but these moments only reinforce the sense of travelling across layers of time — modern technology moving across routes shaped by centuries of trade, migration, and cultural exchange.

As Samarkand receded into the distance, it became clear that Uzbekistan’s story was unfolding as a continuous thread rather than separate destinations. The Silk Road had never been about isolated cities; it had always been about the movement between them.

The journey to Tashkent therefore felt less like a transfer and more like the natural continuation of that story.

Leave a Reply