We began near Petra itself, at Wadi Musa. Just outside the town lies Ain Musa — Moses’ Spring. According to tradition, this is where water flowed after Moses struck the rock. The spring is modest, almost easy to miss, with the rock face rising quietly behind it. There is no attempt to dramatise the site. Water trickles as it always has, and belief rests lightly on the place rather than overwhelming it.

From here, the landscape opened up again. The road carried us past the ruins of Shobak Castle, perched high on a hill. Built by the Crusader king Baldwin I in the early 12th century, it was once known as Montreal. From a distance, its position is unmistakable — defensive, deliberate, watchful. We didn’t linger long. The castle worked better as a presence than as a site to be entered.

Somewhere along the way, we noticed a railway line crossing a small bridge — a remnant of the Hejaz Railway. Once running from Syria towards Mecca and Medina, it spoke of another ambition entirely: movement across vast distances, connection rather than conquest. Even abandoned, it carried a sense of purpose.

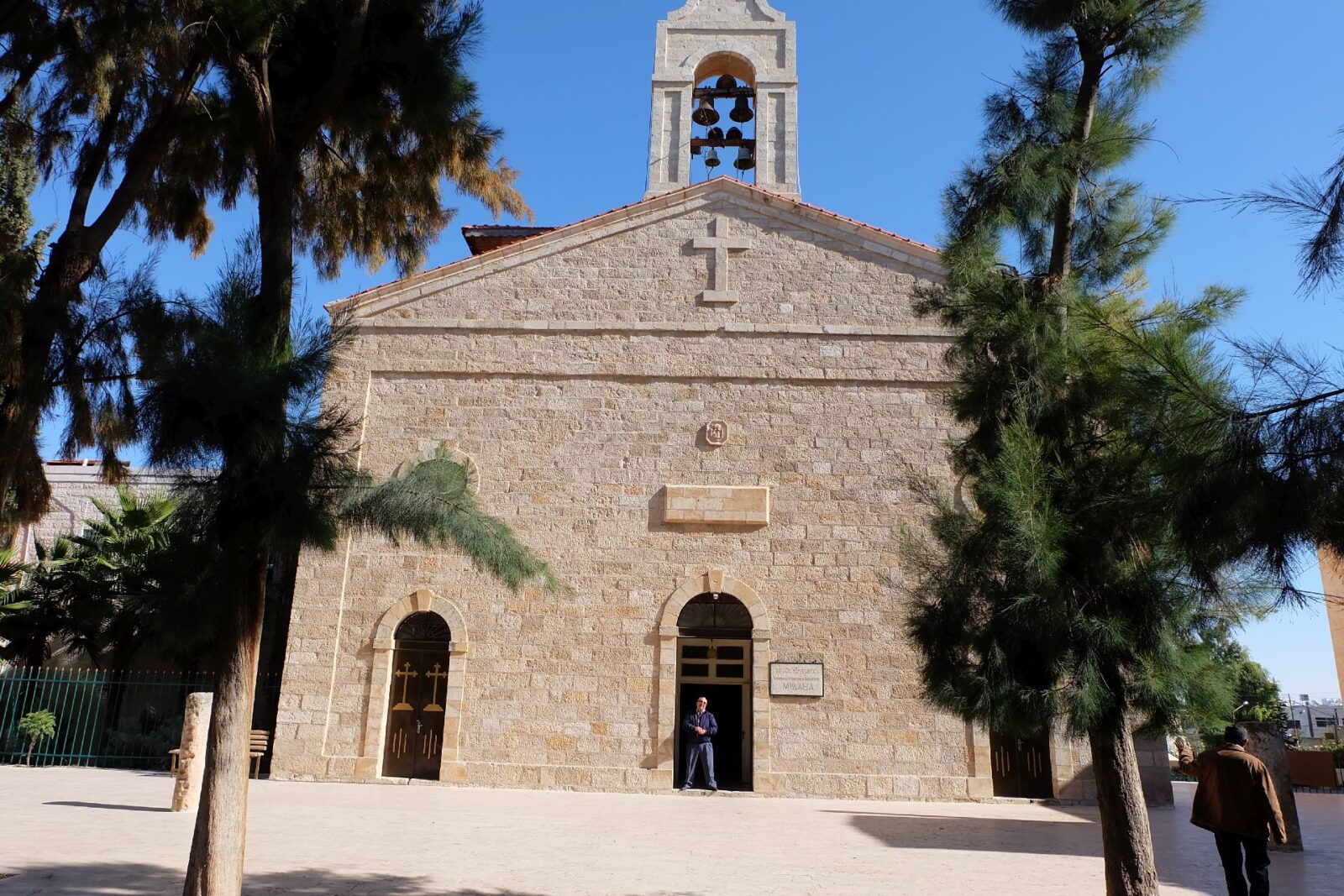

By midday we reached Madaba, a town known less for scale than for detail. Inside the St George Church Madaba, a modest 19th-century structure, the floor holds a map of the Holy Land laid out in mosaic in the 6th century. The map is explanatory only if you want it to be. Otherwise, it works as something quieter — geography rendered by hand, belief translated into pattern.

Nearby workshops continue the mosaic tradition. Watching one take shape — old methods meeting new materials — made Madaba feel less like a museum town and more like a place where skill passes forward. We carried one such piece with us: a Tree of Life, animals arranged on either side according to their nature, a balance suggested rather than enforced.

From Madaba, the road climbed gently to Mount Nebo. This is the place from which Moses is said to have seen the Promised Land. A viewing platform points outward, marking distances to Jericho, Bethlehem, Jerusalem. On a clear day, they say, all are visible. That afternoon, the view was softened by haze, which somehow felt appropriate. The promise here has always been about seeing, not arriving.

At the summit stands the serpentine cross — bronze, symbolic, layered. It merges the image of the serpent raised by Moses with the cross of Christ, compressing centuries of belief into a single form. Nearby, mosaics from the church — closed for renovation — had been carefully relocated under a temporary shelter. Faith, it seemed, adapts when it has to.

From Mount Nebo, the descent is dramatic. In the space of a short drive, the land falls away sharply, dropping from around 800 metres above sea level to nearly 400 metres below it. The Dead Sea lies at the bottom of this fall — the lowest point on Earth.

The Dead Sea doesn’t invite immersion so much as negotiation. Its salinity — around 35 percent — makes floating effortless in theory, but hesitation comes easily. We stepped into the water, felt its density, and stopped short of surrendering to it fully. Stories of burning eyes and stinging wounds have a way of enforcing caution.

Around us, the landscape felt exposed, stripped down to essentials. Minerals line the shore, evaporation outpaces inflow, and the shoreline itself continues to retreat year by year. The Jordan River feeds the sea, marking borders as much as sustaining life. Whether the Dead Sea will stabilise or continue shrinking remains uncertain.

We left Jordan the following day, aware that the journey had ended not with a crescendo, but with a lowering — from carved stone to water, from height to depth. It felt like a fitting conclusion.

Leave a Reply