We thought we knew Petra before we arrived. We had seen it framed endlessly — in photographs, in films, on tourism websites — the same façade repeated until it felt almost symbolic rather than real. That familiarity dissolved quickly. Petra does not reveal itself all at once, and no amount of prior exposure prepares you for the act of walking into it.

We left Amman early and reached Petra by mid-morning. The sky was unsettled, a light drizzle hanging in the air. It felt oddly appropriate. The day resisted clarity, and so did the place.

Petra was established by the Nabataeans sometime around the fourth century BCE, shaped as much by trade as by geography. Caravans passed through here between Arabia, the Mediterranean, and beyond. Later, the Romans absorbed the city, and still later, earthquakes and shifting routes loosened its hold on relevance. By the time it slipped from wider memory, Petra had already learned how to endure without attention.

The walk begins almost quietly. From the visitor centre, the path slopes gently inward. The first monuments appear without ceremony — blocks of stone, carved but unassuming, their purpose unclear unless pointed out. The sense of anticipation builds not because of what you see, but because of what you don’t.

The Siq tightens gradually, sandstone walls rising and folding inward. In places it opens, elsewhere it narrows enough to force awareness of every step. Water channels run along the rock, reminders that this dramatic passage was also engineered, shaped deliberately to protect the city beyond. We hadn’t walked far before Petra began to assert itself — not through monument, but through atmosphere.

Then, almost without warning, the space compresses and releases. Through a narrow slit of light, the Al Khazna appears.

No photograph prepares you for scale. The façade rises more than forty metres, carved directly from the rose-red cliff, its symmetry both precise and improbable. It doesn’t feel decorative. It feels declarative — a statement made in stone, meant to be encountered, not admired from afar. We stood there longer than expected, not speaking much. The drizzle softened the colours, the crowd thinned momentarily, and Petra felt briefly suspended.

Beyond the Treasury, the city opens outward. Tombs line the rock face in long succession, giving the sense of a street rather than a cemetery. A theatre appears, carved rather than built, followed by broad spaces where colonnades once ordered movement. This was not a ceremonial city alone; it was functional, inhabited, shaped by daily life as much as by belief.

Walking Petra is tiring, but not oppressive. The distances are real — kilometres rather than metres — yet the terrain remains forgiving. What exhausts is not effort, but attention. There is always something just ahead, another shift in colour, another carving catching the light differently. We chose not to climb to the Monastery. It felt unnecessary. Petra had already given us more than we could fully absorb.

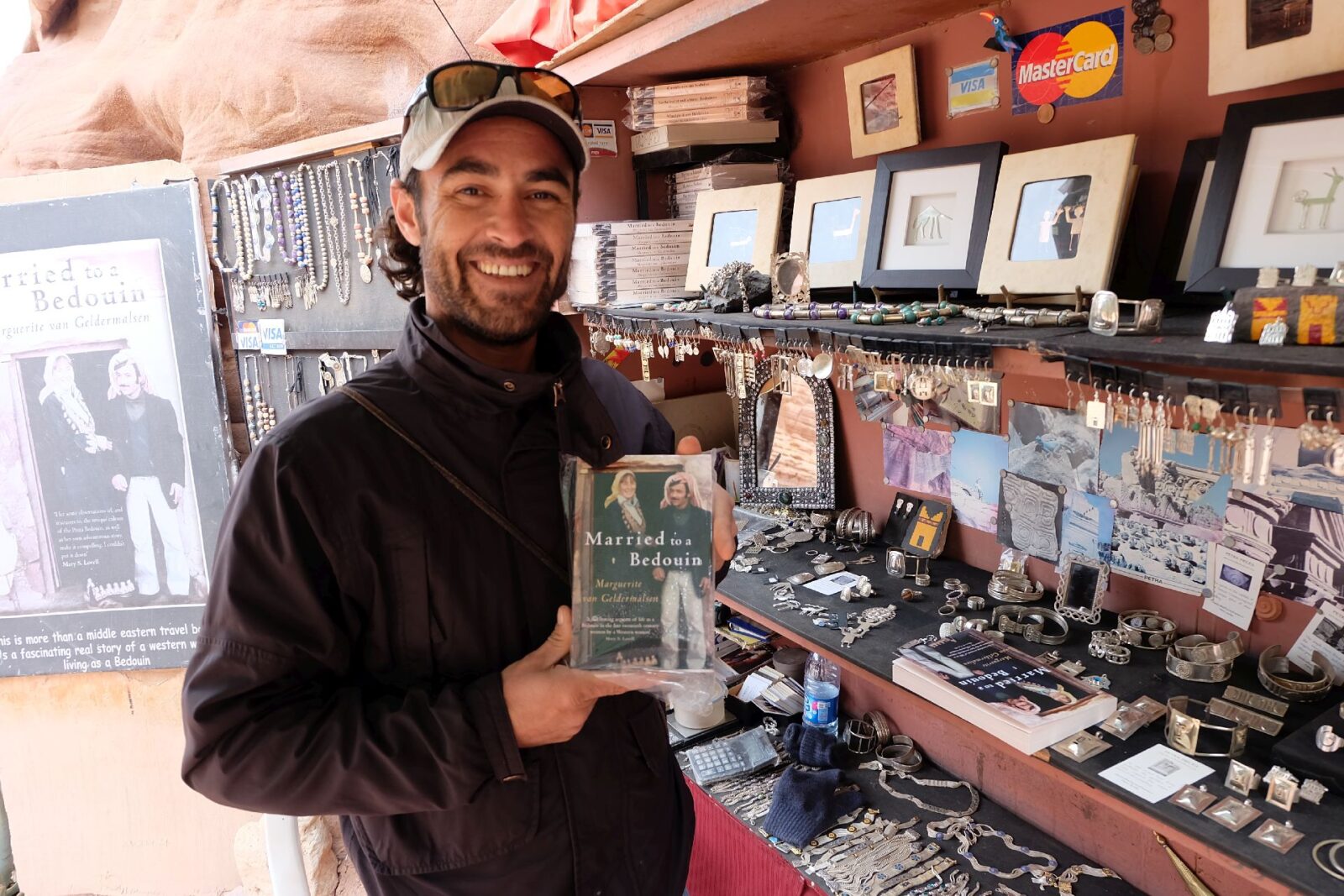

We left in the late afternoon, legs heavy, senses dulled in the best way. But Petra was not finished with us. Petra wasn’t only stone. Along the way, small interactions punctuated the walk.

A few girls, curious and unguarded, noticed P’s bindi and asked where we were from. When she offered them one, curiosity turned into delight — one of them quietly emptied the whole packet into her palm.

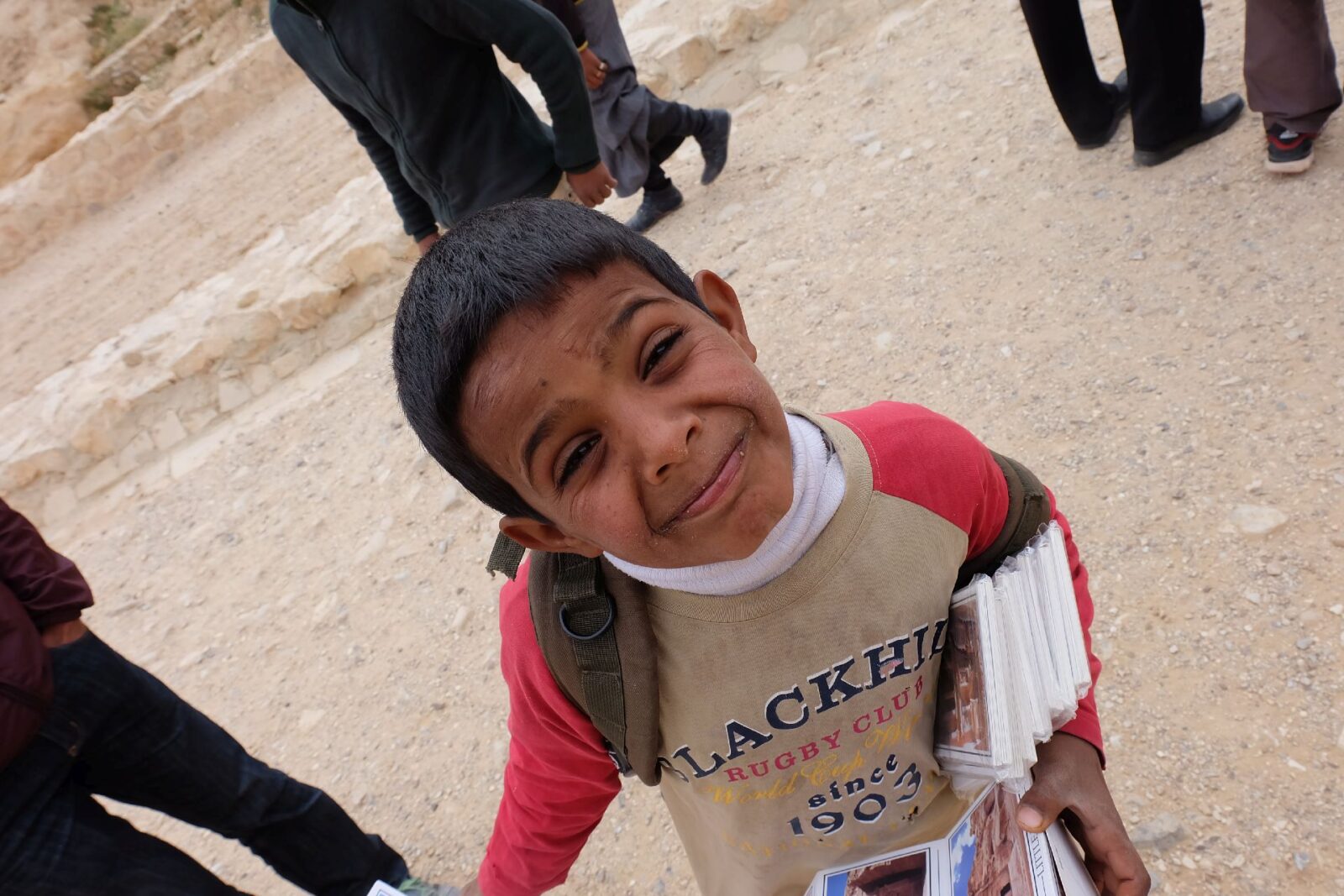

Later, a young boy asked to be photographed, not as a souvenir for us, but as compensation for the wares we didn’t buy. We obliged. It felt fair.

That evening, we returned for Petra by Night. The Siq, lit only by candles placed at intervals, felt narrower, more deliberate. Sound carried differently. At the Treasury, lantern light replaced daylight, and the façade withdrew into shadow, revealing just enough to feel present without spectacle. Tea was offered, music played quietly, a story spoken rather than explained.

Walking back through the darkened Siq later that night, with some candles already extinguished and the cold settling in, Petra felt less like a site and more like a place that tolerated visitors briefly before returning to itself.

It was, without question, the most demanding day of the journey. And also the most generous.

Leave a Reply